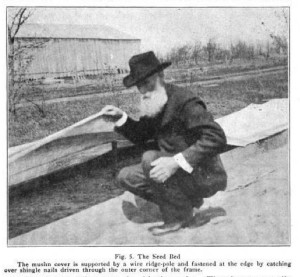

On Christmas Day in 1839, a 61-year-old Wendell farmer named Martin Hagar (sometimes also spelled Hager) made over all of his farm equipment and personal property to his 30-year-old son Charles (shown at left in his own later years). Charles, who had married the year before, agreed to care for his parents, one or both of whom were probably in poor health.

On Christmas Day in 1839, a 61-year-old Wendell farmer named Martin Hagar (sometimes also spelled Hager) made over all of his farm equipment and personal property to his 30-year-old son Charles (shown at left in his own later years). Charles, who had married the year before, agreed to care for his parents, one or both of whom were probably in poor health.

Among the items in Martin’s list of belongings were his livestock (horses, oxen, cattle, and one pig); sled and sleigh; three lumber wagons (suggesting that the family was cutting wood on a fairly large scale); a plow; a grindstone; a mowing machine; and the most expensive single entry on the list, “tobacco sash.”

Wait…what? First of all, what is tobacco sash, exactly? And does its presence in Martin Hagar’s inventory mean that mid-nineteenth-century farmers were actually growing tobacco–a crop that prefers gentle weather and fertile soil–in the rocky, hilly fields of an upland town like Wendell?

To answer the easier question first, tobacco sash is a kind of cold-frame to help tobacco seedlings survive dips in temperature, something particularly important in northern regions. The main tobacco belt in the US is, of course, farther south, centered in Virginia. But as cigars became increasingly popular in the nineteenth century, farmers in the Connecticut Valley and elsewhere began growing tobacco for the outside wrappers of cigars, a lucrative business that continues to play a role in the valley’s agricultural economy today.

To answer the easier question first, tobacco sash is a kind of cold-frame to help tobacco seedlings survive dips in temperature, something particularly important in northern regions. The main tobacco belt in the US is, of course, farther south, centered in Virginia. But as cigars became increasingly popular in the nineteenth century, farmers in the Connecticut Valley and elsewhere began growing tobacco for the outside wrappers of cigars, a lucrative business that continues to play a role in the valley’s agricultural economy today.

But Wendell? It seems unlikely that the Hager family had a great deal of success growing tobacco on their farm on Wendell Depot Road. Tobacco is not listed as one of their commercial crops in the 1850 agricultural census (they were producing a fairly standard mix of corn, potatoes, hay, barley, butter, and meat). The presence of the tobacco sash on Martin’s list, though, suggests that they had ambitions to do more, and to enter more actively into the commercialized and specialized markets that were continuing to expand as the nineteenth century went on.

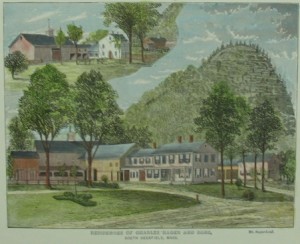

Perhaps those ambitions helped prompt the Hagers to relocate to the richer farmland of Deerfield in 1855. The presence of Charles’s wife’s family there probably also had something to do with it; the couple purchased her parents’ farm near the foot of Sugarloaf Mountain (left) and expanded and updated it, putting an impressive $12,000 into the property. Charles died there in 1880.

The Hagers’ story shows us a family from a relatively modest Wendell farm who were able to move up the economic scale at a time when many farmers were feeling the pinch of commercial competition. The Hagers moved west, but not far west–they remained within Franklin County and became a part of what was then still a very vigorous farm economy along the Connecticut Valley. Wendell was much more on the periphery of that economy, but it was interconnected in many ways. For the Hager family, it may have served as a place to experiment, learn, and take a few risks with new ideas that could keep older farming families on the land.

Acknowledgement

Most of the research for this post was done by Pam Richardson of the Wendell Historical Society. Her account of the Hager family’s history appeared as an article in the Montague Reporter February 13, 2014.

For further reading

- On the relationship between the upland and lowland Connecticut Valley farm towns, see J. Ritchie Garrison, Landscape and Material Life in Franklin County, Massachusetts, 1770-1860 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1991).

- For a brief overview of tobacco cultivation in the area, see the website of the Luddy/Taylor Connecticut Valley Tobacco Museum in Windsor, CT.

- Check out the wiki page on the Hager family and please contribute any additional information there.

Illustrations

- Portrait of Charles Hager and engraving of his farm: “Residents of Charles Hager and Sons, South Deerfield, Mass, South Deerfield, Mass.” as found on Prints Old and Rare website (undated; accessed Aug. 14, 2014).

- Farmer with tobacco sash/cold frame: Coates Preston Bull, Tobacco Growing in Minnesota (St. Paul, MN: University Farm, 1915), p23.