In 1771, the colonial government of Massachusetts surveyed the taxable property in the colony’s 152 towns. Since most people were farmers, the survey focused largely on acreage cleared and cultivated, livestock owned, and the value of the property. Wendell didn’t exist as a separate town yet (it incorporated in 1781) but searching for individual names of people known to have been among the first European-American settlers gives us a glimpse of some of these earliest farms.

In 1771, the colonial government of Massachusetts surveyed the taxable property in the colony’s 152 towns. Since most people were farmers, the survey focused largely on acreage cleared and cultivated, livestock owned, and the value of the property. Wendell didn’t exist as a separate town yet (it incorporated in 1781) but searching for individual names of people known to have been among the first European-American settlers gives us a glimpse of some of these earliest farms.

One of the properties in Wendell (then part of Shutesbury) was being cleared by 28-year-old Ebenezer Johnson, the son of an already-settled Wendell farmer. By 1771, he had cleared just a single acre, back-breaking labor in an era before backhoes and stump-pullers. We don’t know exactly where in town the Johnson family’s properties were, but it’s a safe bet that even after his first acre, Ebenezer had accumulated plenty of material for the kind of stone walls that typically lined an upland farmer’s fields in this part of the state.

This fragment of data about an eighteenth-century Wendell farm family illuminates one of the central facets about agriculture in this Massachusetts “hill town”: thanks to population pressures and political changes, it was already pushing into landscapes that were less than ideally hospitable for the kind of intensive cultivation that European-style farmers practiced. The first colonial settlers, like Native Americans before them, had made use of the flat, fertile bottomlands along river valleys for their farm fields, taking advantage of the continual deposits of nutrients from spring floods and other periodic inundations. Both Native and European farmers also knew about human-assisted forms of manuring and fertilization, but the riverside fields gave them a big boost from natural processes.

In the hill towns, it was another story. Native Americans had likely inhabited these places only seasonally, hunting and perhaps gathering wild foods but not attempting to cultivate plants intentionally. The colonists’ sense of the importance of owning land of their own, coupled with the growth of their population and the greater sense of security along what was then the frontier of European settlement after the end of the French and Indian War in 1763, meant that land less obviously suited to agriculture was increasingly being claimed and settled in the years before the American Revolution. Ebenezer’s acre was part of a process of trying to turn heavily forested, hilly, rocky soil into productive farm fields.

The mainstream story about agriculture in this part of the world is that this was inherently a mistake, and that the long decline of the farm economy in the nineteenth century was a kind of course-correction as New Englanders accepted that they had been over-ambitious in trying to cultivate these kinds of soils. The reforestation of the early twentieth century was a part of this course-correction, giving us the landscape we see today of old stone walls running through new-growth forests.

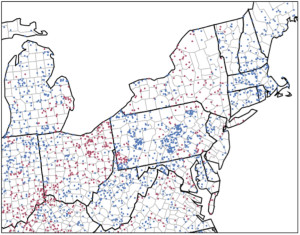

But people have continued to farm in these places and often to make some kind of living at it. And today’s food movement has seen a return to the kind of small-scale intensive farming that Ebenezer Johnson was working toward. The map at left shows blue dots where there has been an increase in the number of farms, bucking the general trend of decline (shown by red dots). Much of the blue appears in older upland areas of the northeast, where new and smaller-scale farmers are once again finding opportunities to access less high-priced land. (In an ironic twist, some of this land is in places that have been preserved for their scenic or nostalgic qualities, reflecting a later era’s sense that farming was indeed finished in these areas.)

But people have continued to farm in these places and often to make some kind of living at it. And today’s food movement has seen a return to the kind of small-scale intensive farming that Ebenezer Johnson was working toward. The map at left shows blue dots where there has been an increase in the number of farms, bucking the general trend of decline (shown by red dots). Much of the blue appears in older upland areas of the northeast, where new and smaller-scale farmers are once again finding opportunities to access less high-priced land. (In an ironic twist, some of this land is in places that have been preserved for their scenic or nostalgic qualities, reflecting a later era’s sense that farming was indeed finished in these areas.)

In between Ebenezer’s laboriously-cleared acre and the return movement of farmers to the hill towns lies the story of what happened when the new eighteenth-century upland farms hit the even newer nineteenth-century industrial capitalist economy, with its expanded demands, technologies, and promises of wealth–a story we can trace through the efforts of later townspeople to maintain the farms their eighteenth-century forebears had so painstakingly carved out on the rocky hills.

For further reading:

- On the shift from Native to European land use in New England, the classic text is William Cronon’s Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (New York: Hill and Wang:2003[1983]).

- On colonial settlement in both lowland and upland places, see Brian Donahue, The Great Meadow: Farmers and the Land in Colonial Concord (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004) and J. Ritchie Garrison, Landscape and Material Life in Franklin County, Massachusetts, 1770-1860 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1991).

- Harvard University has digitized the 1771 Massachusetts Tax Valuation lists, as originally prepared by Bettye Pruitt.

- The famed dioramas of the Harvard Forest in nearby Petersham, Massachusetts help us to imagine how these hill towns looked in various periods. One of the earliest depicts a settler clearing land as Ebenezer Johnson would have done.

- On probable Native patterns of use and occupation of the lands that are now the town of Wendell, see the 1982 Massachusetts Historical Commission “Reconnaissance Survey” for the town and Chapter 1 of Wendell: the (his)story of a hill town by Jean Forward.

- Check out the wiki page on the Johnson family and please contribute any additional information there.

Illustrations:

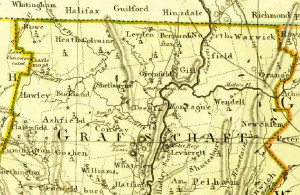

- A German map of Massachusetts in 1792 shows Franklin County’s towns shortly after the Revolution.

- Map showing changes in number of farms between 2002 and 2007 (blue dot = gain of 20 farms, red = loss of 20 farms): National Agricultural Statistics Service, US Department of Agriculture.