In the fall of 1853, Dr. Lucius Cook wrote a letter to the newspaper describing his great success in growing carrots on 3/4 of an acre in the center of Wendell. Subsequently reprinted in The New England Farmer, his letter described how he had been trying for two years to convert a hayfield to vegetable production. An initial crop of potatoes had failed due to disease. The following year he lost most of his corn to worms and then had such a large yield of rutabagas that his horses (the only animals that would eat them) couldn’t get through all of them before the spring, and Cook ended up throwing most of them onto the compost pile.

In the fall of 1853, Dr. Lucius Cook wrote a letter to the newspaper describing his great success in growing carrots on 3/4 of an acre in the center of Wendell. Subsequently reprinted in The New England Farmer, his letter described how he had been trying for two years to convert a hayfield to vegetable production. An initial crop of potatoes had failed due to disease. The following year he lost most of his corn to worms and then had such a large yield of rutabagas that his horses (the only animals that would eat them) couldn’t get through all of them before the spring, and Cook ended up throwing most of them onto the compost pile.

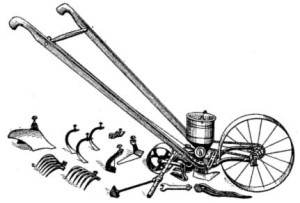

But with the carrots he hit the jackpot. He added about 30 loads of horse manure to the soil, invested in a new seed drill to plant the tiny seeds, and hired a crew to do the planting (and remove some of the stones that inevitably worked their way to the surface of the field, Wendell being known as a “rough, hilly town” in the words of the New England Farmer‘s correspondent). In the fall, the harvest repaid Cook’s costs handsomely, with a yield of 16 tons or 651 50-pound bushels. It isn’t clear whether he was selling them for human or animal consumption or both, but he was delighted to report that the carrots fetched a good price and he was even able to make a little extra by selling “the tops as they lay in the field,” clearing a net income of $100–perhaps around $3,000 in today’s dollars.

However, Amherst-born Lucius Cook wasn’t primarily a farmer. His farming ventures were too small to be counted in the agricultural census for 1850, and his main income was derived from his work as the town’s doctor and first postmaster. He was also a justice of the peace, and his wife, Fidelia Hayward Cook, was a noted poet and later a literary editor (she championed the work of Emily Dickinson and other women poets at the Springfield Republican in the 1860s). The Cooks were among the small professional class in Wendell, not notably wealthier but certainly somewhat distinct from the full-time farmers who still made up the great majority of the town’s population. Why, then, did Cook think it was worth making a fuss about his $100 worth of carrots in a regional agricultural journal?

The answer has to do with the growing perception that New England farms, particularly in upland places like the Connecticut River Valley hill towns, were in decline by the middle of the 19th century. The evidence shows that the perception and reality were somewhat at odds. Farmers in the region were continuing to farm productively and to adapt to the new demands of more commercialized and specialized markets (for instance, shifting to growing hay for the demands of urban horse-powered transportation after the coming of the railroad undercut the previously-profitable trade in taking fattened cattle to city markets via the roads).

But as Hal Barron has shown in his detailed study of similar small farming towns in Vermont, agriculture was a maturing rather than an expanding sector at that point. Not all sons and daughters of farmers could expect to inherit land and carry on farming; industrial jobs were beginning to be more widely available; and perhaps most important, the seemingly limitless profits promised by industry and speculation made the slower, more settled business of farming seem poky and unexciting to many younger New Englanders. Industrial ventures and capital markets were the sexy dot-com start-ups of their day, and when it came to a contest of images, farming had a hard time competing.

This caused considerable anxiety among politicians, reformers, and the intelligentsia, not least because of the sectional tensions of the pre-Civil War years. Many worried that the values that were widely attached to farming as a way of life–independence, self-discipline, hard work–were being lost in the rush toward faster, bigger profits. There was also concern that the north could lose much of its population to the new western states and territories still opening up. Wendell’s population was still holding steady–the sharp drop didn’t come until after the Civil War, and in 1850 there were still 920 people in the town, about the same as today. But the fear was there, and it prompted a great deal of activity designed to defend and improve farming in the northeast, especially in smaller, more “marginal” places.

![]() It’s surely not a coincidence that the Franklin County Agricultural Society was founded in 1850, the same year that Lucius Cook started trying to grow vegetables in a former hayfield. Cook was a member of the Society, and likely read not only The New England Farmer but other forward-looking farm journals filled with advice about how to make small farms more economically viable. Cook’s carrots weren’t just about making money or feeding his horses. They were an attempt to demonstrate that farmers who were willing to try new ventures and adopt modern techniques (like the seed drill) could find new sources of profit and maintain their central place in the region’s economy.

It’s surely not a coincidence that the Franklin County Agricultural Society was founded in 1850, the same year that Lucius Cook started trying to grow vegetables in a former hayfield. Cook was a member of the Society, and likely read not only The New England Farmer but other forward-looking farm journals filled with advice about how to make small farms more economically viable. Cook’s carrots weren’t just about making money or feeding his horses. They were an attempt to demonstrate that farmers who were willing to try new ventures and adopt modern techniques (like the seed drill) could find new sources of profit and maintain their central place in the region’s economy.

It’s not clear whether Cook’s experiment carried any weight with his townsmen. Cook himself, already “a stoutly-built and very corpulent man” according to one obituary, moved to Erving shortly before his early death at 44, five years after he recorded his bumper crop of carrots. But his 1853 letter does give us a window into some of the conversations that were taking place around farming in the period, and some of the strategies that farmers and their allies were experimenting with in changeable and uncertain times.

Further reading:

- On perceptions vs. realities in small New England farm towns in this period, see Hal S. Barron, Those Who Stayed Behind: Rural Society in Nineteenth-Century New England (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984). On agricultural as a maturing sector within a recognition of ecological limits in an earlier era, see Brian Donahue, The Great Meadow: Farmers and the Land in Colonial Concord (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004, especially Chapter 8, “A Town of Limits”).

- On the literary career of Fidelia Hayward Cook after her husband’s death, see Judith Scholes, “Emily Dickinson and Fidelia Hayward Cooke’s Springfield Republican,” The Emily Dickinson Journal, Volume 23, Number 1, 2014, pp. 1-31.

- Check out the wiki page on Lucius Cook’s family and contribute any additional information there.

Illustrations

- Carrots: Commercial Gardening: A Practical and Scientific Treatise for Market Gardeners, Vol. 4, Fig. 468 (ed. John Weathers, pub. The Gresham Publishing Co., 1913)

- Combination Hand Plow, Harrow, Cultivator and Seed Drill from M.G. Kains, Culinary Herbs: Their Cultivation, Harvesting, Curing and Uses (New York: Orange Judd Company, 1912, p. 46)

- Franklin County Agricultural Society seal found in 1855 report of the society.